The Illustrated Man

He opened his hand. On his palm was a rose, freshly cut, with drops of crystal water among the soft pink petals. I put my hand out to touch it, but it was only an Illustration…

Ray Bradbury, The Illustrated Man, 1951

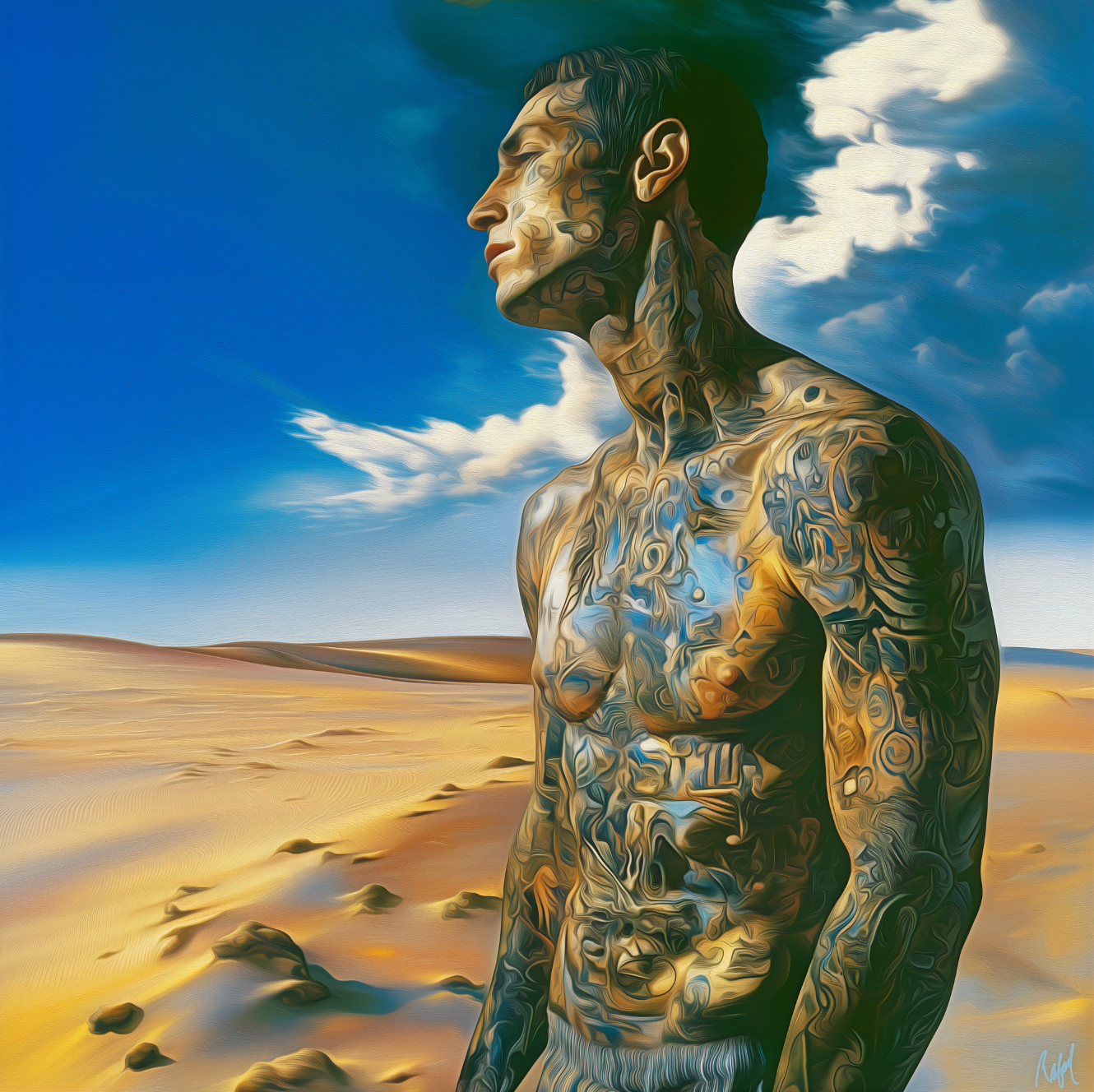

Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man is not a novel, but it holds together like one. What unites its eighteen stories is a single, indelible image: a man whose body is covered in living tattoos—each a window into another world. By day they lie in stillness; by night they awaken, shimmer, and shift, murmuring silent tales of wonder, melancholy, and dread.

The illustrated man is a drifter, a former carnival worker, condemned to search for the witch who inked his flesh decades ago—so that he might kill her. The tattoos were never ornament. They were a curse. They tell stories of astronauts and exiles, fire balloons hovering above alien plateaus, veldt grasses burning under artificial suns, the endless rain of Venus. But the most terrible image is not a spectacle—it is a blank space on his back. When the final story fades, the gaze is drawn there. Slowly it stirs, gathering shape, until it reveals a single vision: the death of the one who looks.

That is why he wanders. That is why he is feared. That is why, in desperation, he once tried to burn the tattoos away with acid—but they only deepened.

In Bradbury’s hands, technology is never simply a marvel; it is a mirror. The future is not an escape but a sentence. His frame story makes the illustrated man more than a character—he becomes an emblem of storytelling itself. His flesh is a living page, and each reader becomes part of the curse.

Like Cain, he is marked not merely as punishment, but as premonition. He carries the weight of all possible futures, and with it, unbearable solitude. To look at him is to confront the terrifying weight of narrative, the knowledge of all that might be, and all that will be. His tales do not merely entertain—they whisper a deeper truth: that the burden of foreknowledge is divine and never meant for mortals.

As a child, I feared that to know all things would be to live without surprise. If every page was already read, what joy could there be in a story?

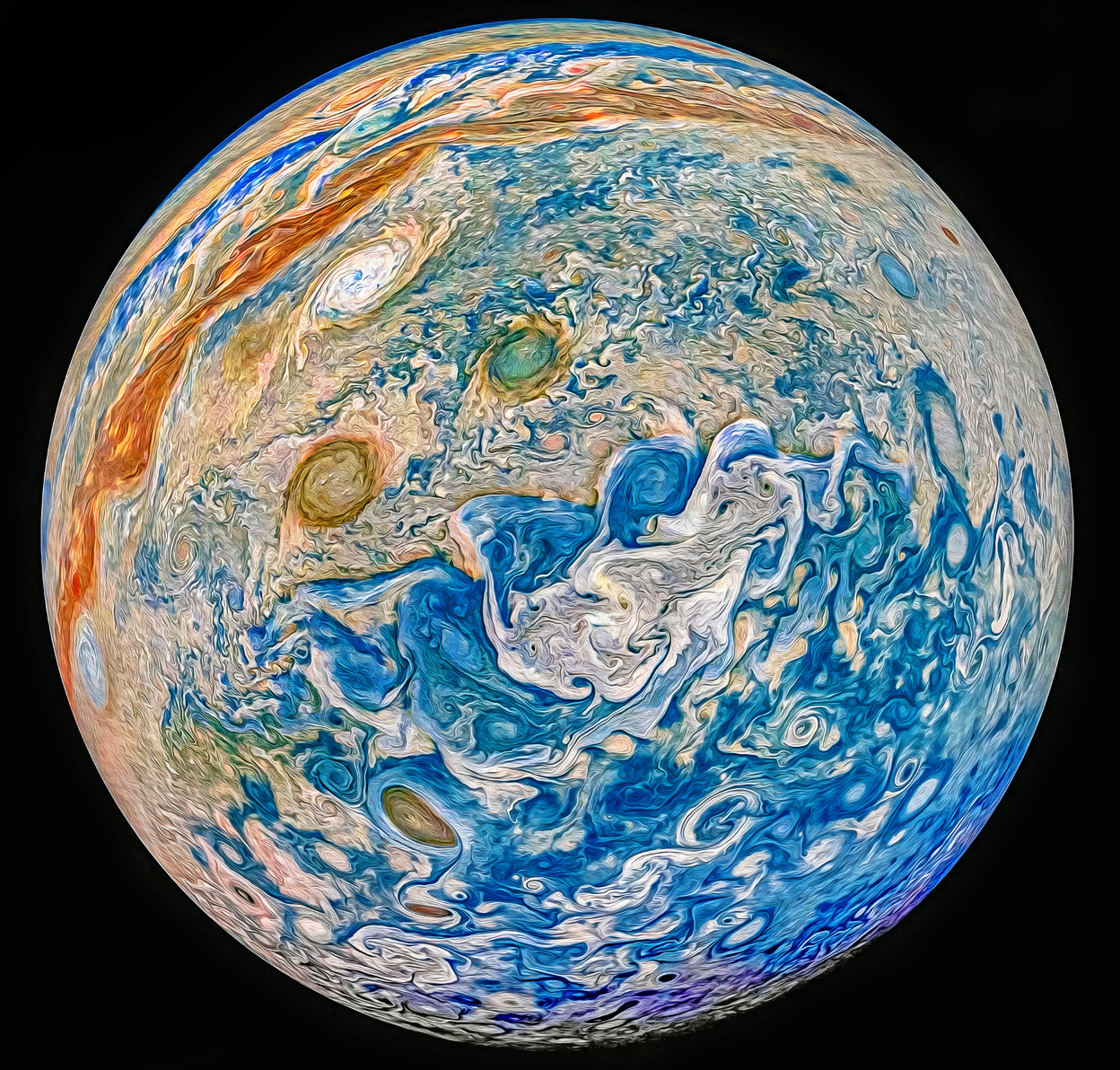

The scriptures state that God dwells upon a globe like a sea of glass and fire, where all things are manifest, past, present, and future. Yet He has veiled this vision from us—not out of cruelty, but mercy. For no creature could love, let alone trust, a Creator who had already revealed the manner of its end.