Your cart is currently empty!

All things have their likeness… Moses 6:63

The Magic Flute, composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in the final year of his life, is often dismissed for its fantastical elements: enchanted instruments, talking animals, and a libretto that defies convention. Yet beneath its fairy-tale surface lies a dense web of spiritual symbolism. This is no accident. Mozart and his librettist, Emanuel Schikaneder, were Masons steeped in Enlightenment philosophy. Together, they created an opera that serves not merely as entertainment but, from a Latter-day Saint perspective, as a dramatized and veiled enactment of initiation and covenantal ascent.

At its heart, The Magic Flute is a journey—one that parallels the narrative of the Fall and redemption. It tells the story of Tamino and Pamina, two youthful seekers who begin in innocence but are soon cast into a world of trial through deception. They are separated, tested, and ultimately purified—not as individuals, but as a couple, united in knowledge and love. Their triumph comes only after they have been introduced into a sacred priesthood and passed through multiple trials.

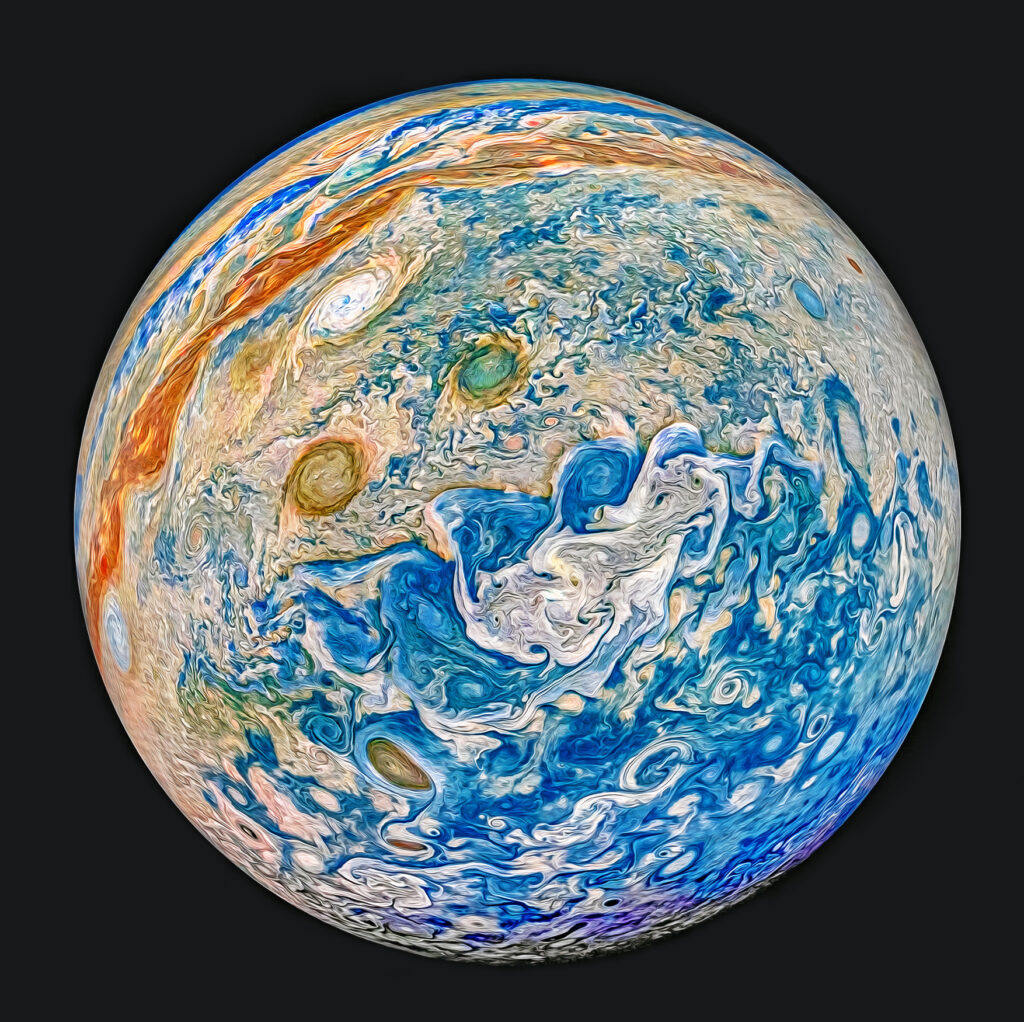

It begins with Tamino, lost in a foreign land, pursued by a serpent. He is rescued by three mysterious women—emissaries of the Queen of the Night (depicted in the piece). The Queen entices Tamino with a mission: to rescue her daughter, Pamina, allegedly imprisoned by the wicked Sarastro. She offers glory and love but conceals the truth. Tamino accepts and is given a magical flute for protection.

As Tamino enters Sarastro’s realm, he finds not tyranny but order and light. Sarastro is no captor; he is the High Priest of the Temple of the Sun. The Queen, who had appeared as a grieving mother, is revealed to be a figure of chaos and darkness. The opera’s central theme is thus a theological inversion—a deliberate reversal of apparent good and evil. Sarastro does not compel Tamino or Pamina; he invites them to choose light of their own free will. But entry into the temple requires purification—through silence, fire, and water. These trials are not mere obstacles, but sacraments—means of refinement.

The parallels with scripture are striking. The Queen of the Night offers a plan without covenant—not unlike Lucifer’s proposal in the premortal council to save all without agency. She appeals to affection but denies law. She promises liberation but delivers bondage. Sarastro offers light—but through sacrifice and submission to divine order.

The number three permeates the opera: three chords open the overture— evoking the triple knocks used in Masonic rites to request entrance into sacred knowledge, three ladies appear, three temples stand at the center of the stage, three trials must be endured. For Freemasons, the triangle is a symbol of harmony and divine order. In Latter-say Saint theology it foreshadows the marriage covenant, with the husband and the wife at each corner of the triangle base and Christ at the apex. The trials Tamino faces are not merely obstacles—they are a ritual of descent and ascent, echoing mortal progression towards enlightenment.

Even the music seems to follow this archetype. The opera was written in E-flat major, a key with three flats. When the Queen of the Night appears, the key darkens into C minor—symbolizing descent and deception. But as Tamino completes his journey, Mozart returns to E-flat major, now elevated—literally, as the bottom note of the chord is lifted an octave. These changes in key mirror symbolically the three degrees of progression: innocence (premortal state), trial (mortal), and redemption (exaltation).

Thus, while The Magic Flute represents musically perhaps Mozart’s greatest achievement, it is also a sacred allegory disguised in operatic form. Its message, hidden in myth and melody, is one we recognize: that through priesthood, through covenant, and through conjugal love sanctified by trial, God’s children may pass through the veil—emerging from darkness into the divine.